A few days before the international semi-finals, the American embassy in Karachi handed her a yellow slip: visa denied.

Javeria Shah went home, opened her laptop, and kept preparing. Though most finalists would compete on stage in San Francisco, she had to compete from her mother's house in Karachi, betting on the Wi-Fi.

By the end of 2025, she'd won the first Clay Cup — a global competition for GTM engineers that drew hundreds of contestants from dozens of countries. Her photo appeared in Times Square. She started her first business. But it wasn’t always easy.

“When you grow up in a third world country,” Javeria said, “there is a lot that comes with that: safety, security, social pressure.” She’d been robbed twice at gunpoint, and the social pressure to choose marriage over career ambitions was rampant.

Some people said that her goals were bold, but that never included her family. At home, her father, grandfather, and uncle were all engineers. She grew up building circuits on breadboards for fun, graduated college with a degree in electronics, and aimed for a career in robotics. Then the pandemic arrived and wrecked the job market.

Waiting around wasn’t an option, so Javeria took an SEO job to start learning about growing a business. She eventually moved to tech sales, where she eventually got connected to Ricky Pearl, a Clay Club lead in Australia who introduced her to Clay. “I didn’t know anything about it,” she said. “But I knew I could figure it out.”

She realized that most sales workflows were fragile operations held together by spreadsheets and manual copying and pasting. Her technical training allowed her to turn that chaos into automations — much more easily than many others in the field.

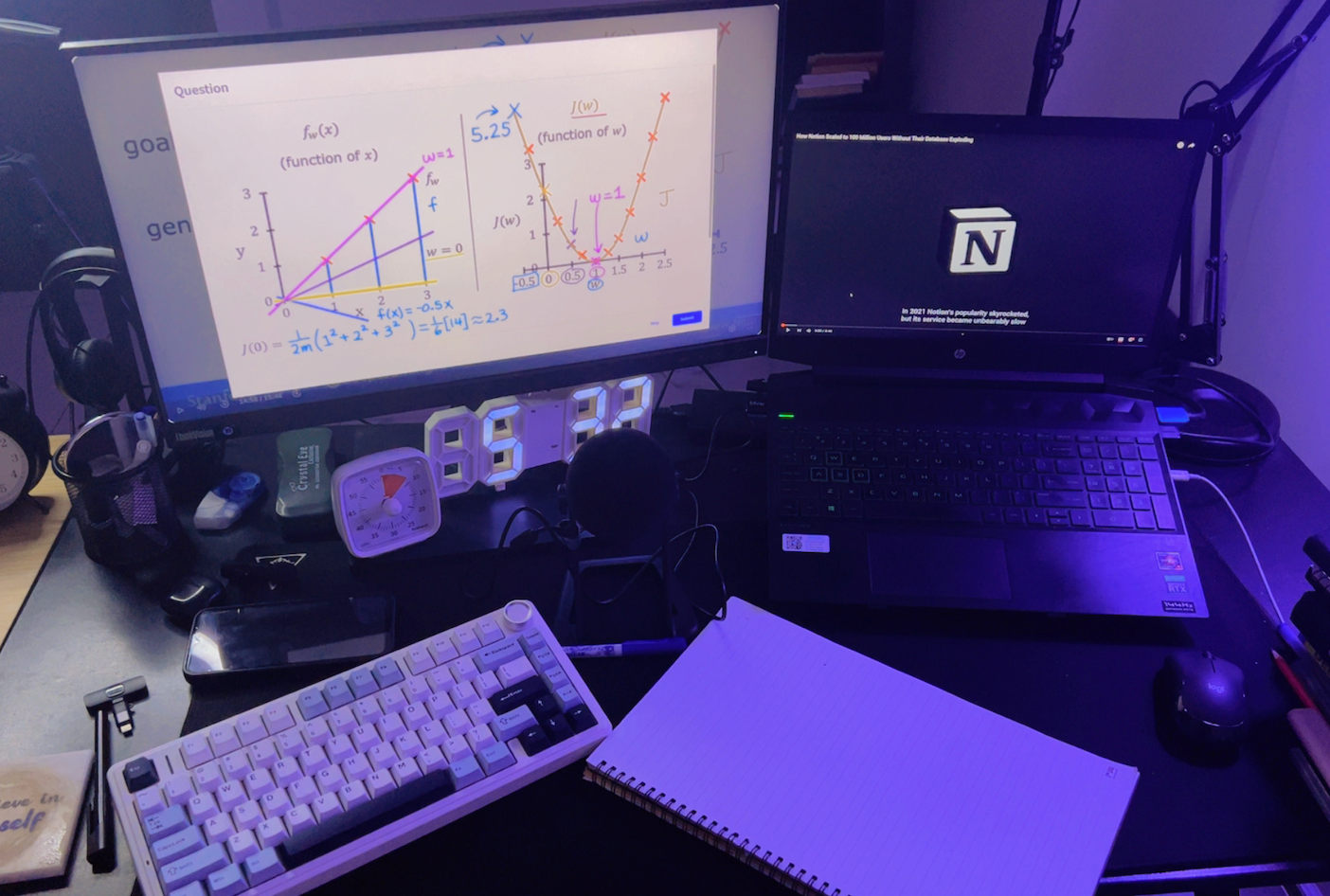

As she started to realize the potential impact and earnings, Javeria started going all in on this new career path. She skipped weddings to avoid unwanted questioning and spent late nights handling US-based clients. “I wanted to craft my own life and have financial independence. If I was, someday, going to be with a man, my mother taught me to have it be by choice, not compulsion.”

By the time Clay announced the Clay Cup in 2025, she’d been training for it without knowing it. Contestants got a prompt, a timer, and a short window to build something real. Javeria’s local Clay Club asked if she wanted to represent Karachi, Pakistan.

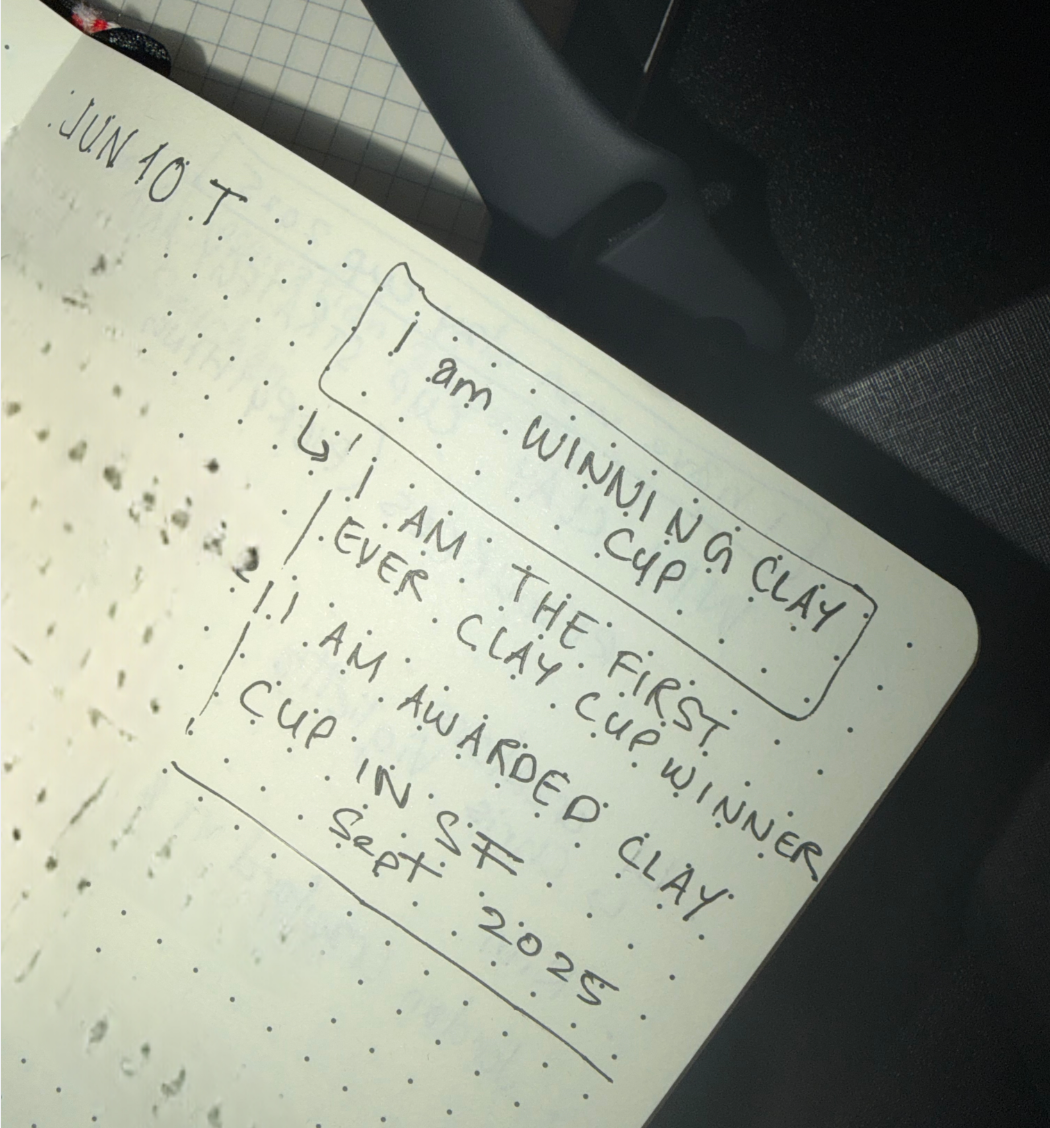

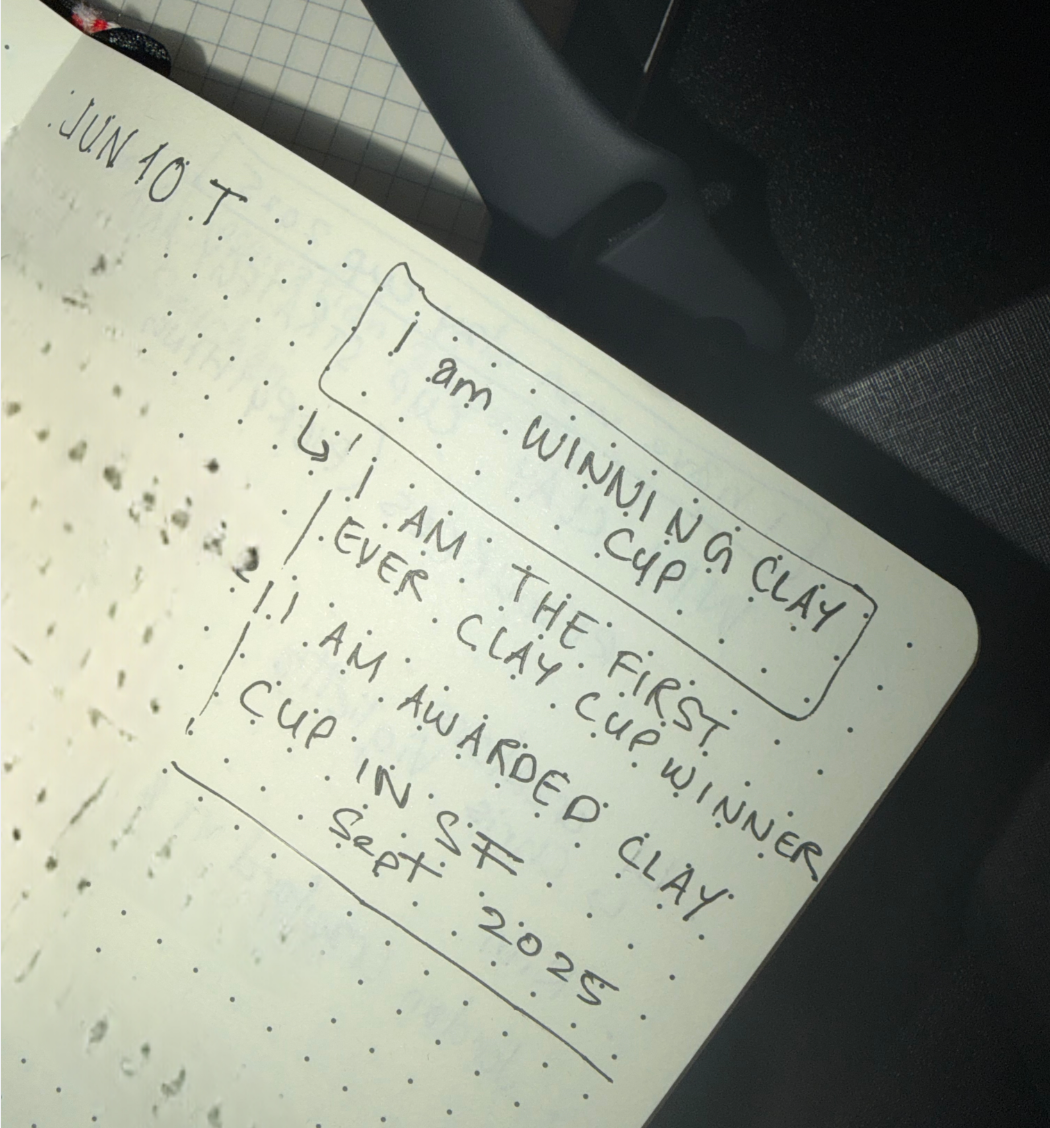

On her first day, she wrote a line in her journal: It’s September 2025, and I have won the 2025 Clay Cup.

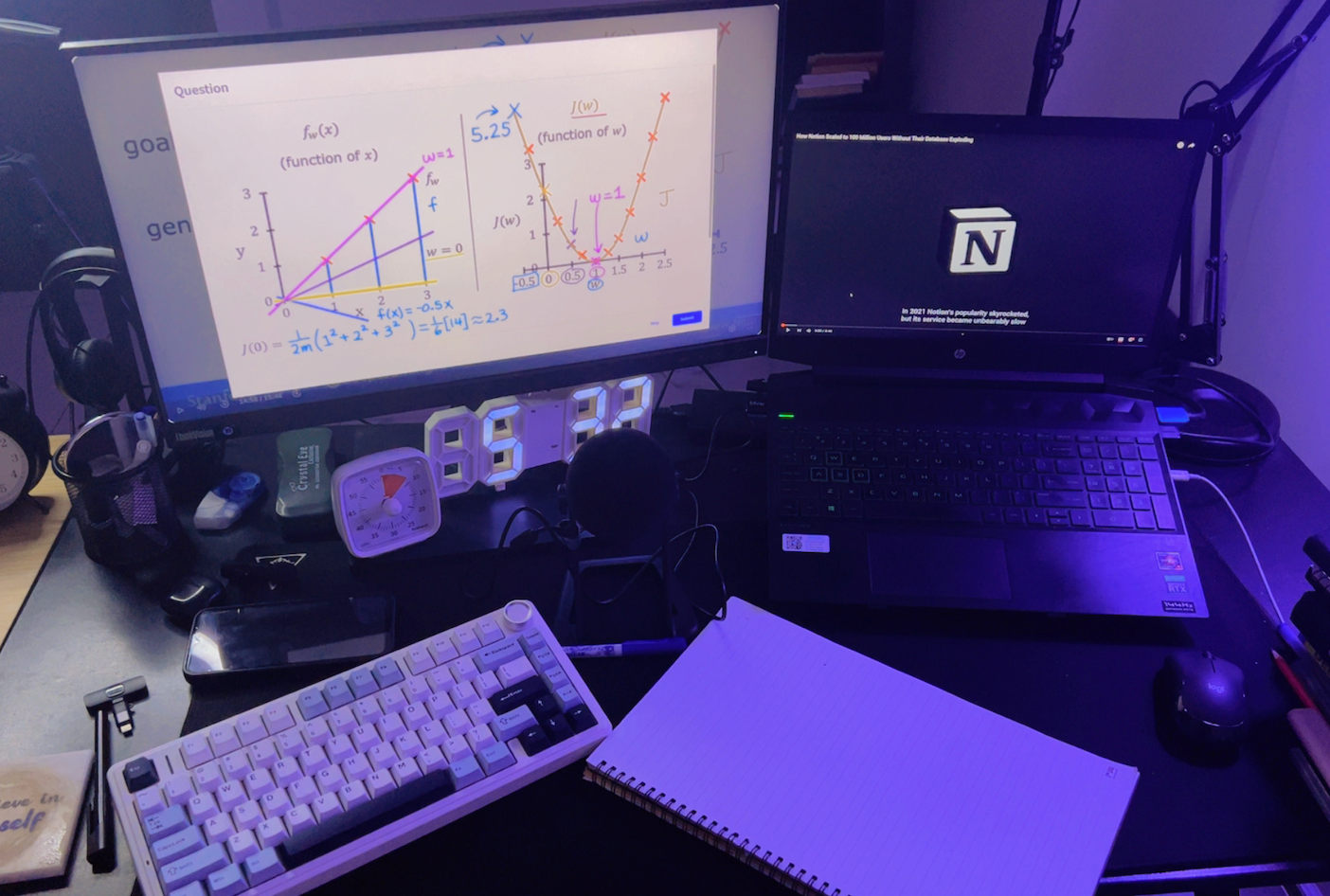

Javeria was already studying about AI and technology for a few hours a day. Now, she added Clay to the mix. She watched everything Clay put out — Clay University, case studies, YouTube videos. “If I wasn’t prepared enough, I told myself I couldn’t complain,” she said. “I had to prepare more than my competitors.” Before each round, she researched the judges carefully, trying to understand what they valued.

Competing remotely from Pakistan came with challenges other finalists didn’t have to consider. An hour before one of her rounds, her internet went out, forcing her to rush to the nearest coworking space just to stay in the competition.

Before every round, she repeated a prayer her mom taught her: “Rabbi yassir, wala tu’assir, watammim bil khayr” — Oh God, make it easy for me. Don’t make it hard for me. And make it end well.

By the time the finals began, after multiple incidents with shaky WiFi and one denied visa, finishing at all felt like hard work. By the end of the round, however, with hundreds of people watching, she had won.

“I went blank,” she said. It was 2 AM in Pakistan. Then her sisters ran into the room and her husband drove over immediately. Her coworkers had been watching live, and messages poured in. “It didn’t feel like it was only my win,” she said. “It felt like a win for everyone who had been there for me.”

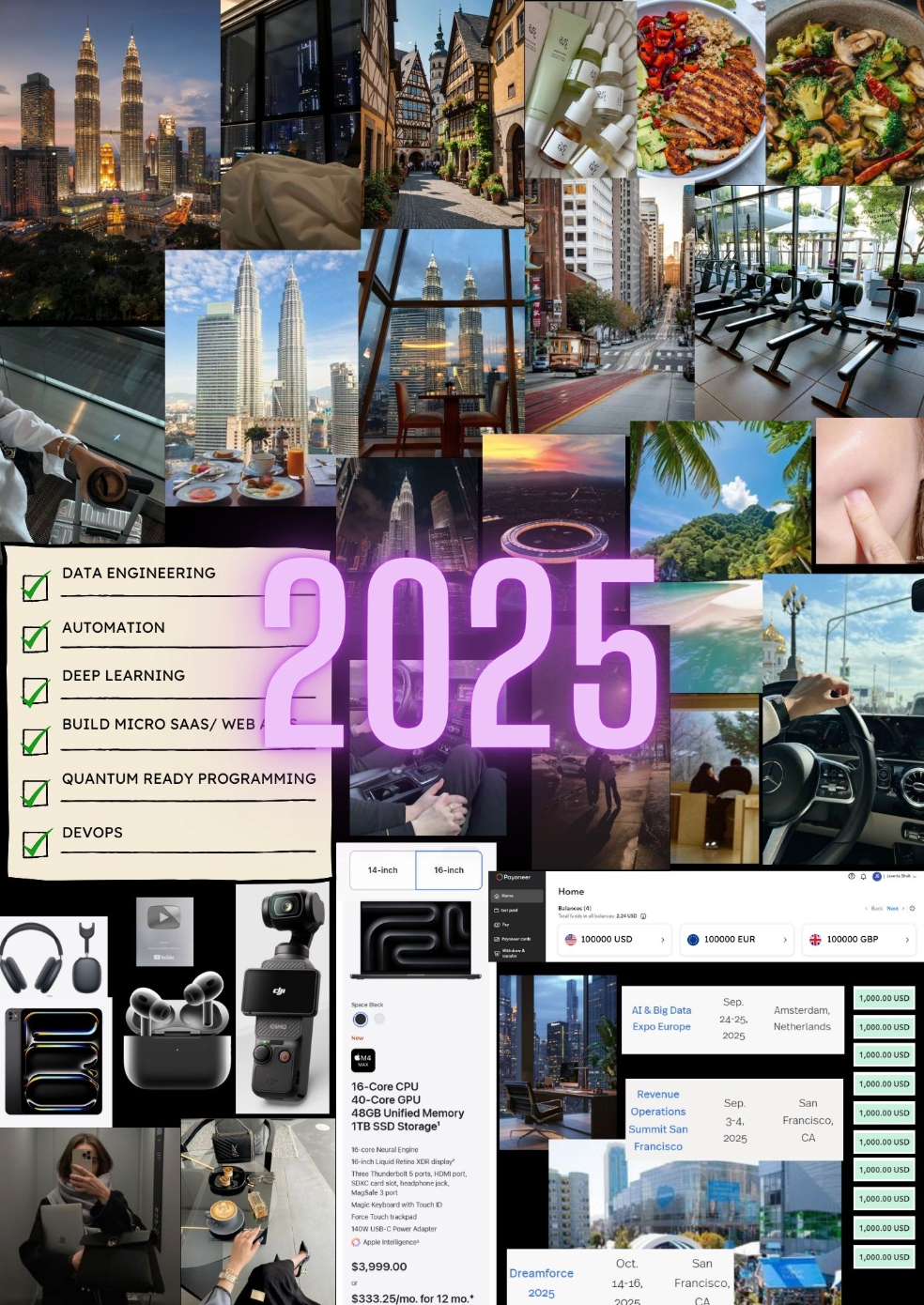

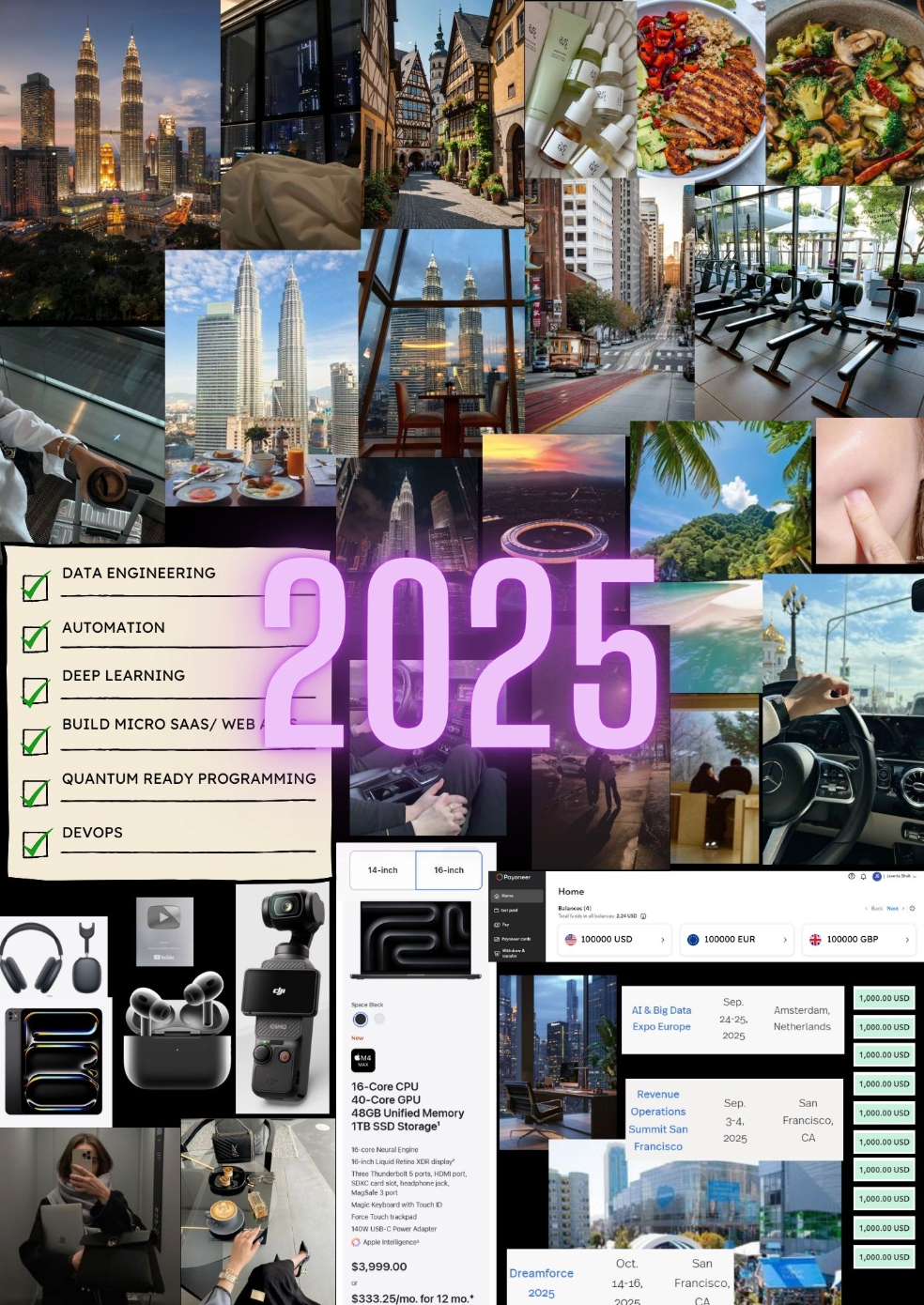

After that, the attention arrived fast. “I achieved so much on my 2025 vision board,” she said. “I made enough money to buy a professional camera, a MacBook, an iPad, everything that I’d wanted. I traveled to Sri Lanka and Thailand. I moved to a beautiful new home in Islamabad, turned down a $150K/year job offer, and started a business with my husband. My credibility increased a lot.”

Javeria practices a different kind of engineering than the one she imagined in college: GTM engineering. “There was no way I could have come from electronics engineering to GTM engineering if I had chosen a conventional path,” she said. “But I listened to my heart, and whatever opportunity I got, I tried to seize it.”

Her 2026 vision board includes scaling her business to $1M, earning a Master’s in AI, getting to Forbes 30 Under 30. “If I want something,” she says, “I will find a way.”

A few days before the international semi-finals, the American embassy in Karachi handed her a yellow slip: visa denied.

Javeria Shah went home, opened her laptop, and kept preparing. Though most finalists would compete on stage in San Francisco, she had to compete from her mother's house in Karachi, betting on the Wi-Fi.

By the end of 2025, she'd won the first Clay Cup — a global competition for GTM engineers that drew hundreds of contestants from dozens of countries. Her photo appeared in Times Square. She started her first business. But it wasn’t always easy.

“When you grow up in a third world country,” Javeria said, “there is a lot that comes with that: safety, security, social pressure.” She’d been robbed twice at gunpoint, and the social pressure to choose marriage over career ambitions was rampant.

Some people said that her goals were bold, but that never included her family. At home, her father, grandfather, and uncle were all engineers. She grew up building circuits on breadboards for fun, graduated college with a degree in electronics, and aimed for a career in robotics. Then the pandemic arrived and wrecked the job market.

Waiting around wasn’t an option, so Javeria took an SEO job to start learning about growing a business. She eventually moved to tech sales, where she eventually got connected to Ricky Pearl, a Clay Club lead in Australia who introduced her to Clay. “I didn’t know anything about it,” she said. “But I knew I could figure it out.”

She realized that most sales workflows were fragile operations held together by spreadsheets and manual copying and pasting. Her technical training allowed her to turn that chaos into automations — much more easily than many others in the field.

As she started to realize the potential impact and earnings, Javeria started going all in on this new career path. She skipped weddings to avoid unwanted questioning and spent late nights handling US-based clients. “I wanted to craft my own life and have financial independence. If I was, someday, going to be with a man, my mother taught me to have it be by choice, not compulsion.”

By the time Clay announced the Clay Cup in 2025, she’d been training for it without knowing it. Contestants got a prompt, a timer, and a short window to build something real. Javeria’s local Clay Club asked if she wanted to represent Karachi, Pakistan.

On her first day, she wrote a line in her journal: It’s September 2025, and I have won the 2025 Clay Cup.

Javeria was already studying about AI and technology for a few hours a day. Now, she added Clay to the mix. She watched everything Clay put out — Clay University, case studies, YouTube videos. “If I wasn’t prepared enough, I told myself I couldn’t complain,” she said. “I had to prepare more than my competitors.” Before each round, she researched the judges carefully, trying to understand what they valued.

Competing remotely from Pakistan came with challenges other finalists didn’t have to consider. An hour before one of her rounds, her internet went out, forcing her to rush to the nearest coworking space just to stay in the competition.

Before every round, she repeated a prayer her mom taught her: “Rabbi yassir, wala tu’assir, watammim bil khayr” — Oh God, make it easy for me. Don’t make it hard for me. And make it end well.

By the time the finals began, after multiple incidents with shaky WiFi and one denied visa, finishing at all felt like hard work. By the end of the round, however, with hundreds of people watching, she had won.

“I went blank,” she said. It was 2 AM in Pakistan. Then her sisters ran into the room and her husband drove over immediately. Her coworkers had been watching live, and messages poured in. “It didn’t feel like it was only my win,” she said. “It felt like a win for everyone who had been there for me.”

After that, the attention arrived fast. “I achieved so much on my 2025 vision board,” she said. “I made enough money to buy a professional camera, a MacBook, an iPad, everything that I’d wanted. I traveled to Sri Lanka and Thailand. I moved to a beautiful new home in Islamabad, turned down a $150K/year job offer, and started a business with my husband. My credibility increased a lot.”

Javeria practices a different kind of engineering than the one she imagined in college: GTM engineering. “There was no way I could have come from electronics engineering to GTM engineering if I had chosen a conventional path,” she said. “But I listened to my heart, and whatever opportunity I got, I tried to seize it.”

Her 2026 vision board includes scaling her business to $1M, earning a Master’s in AI, getting to Forbes 30 Under 30. “If I want something,” she says, “I will find a way.”

.png)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)